By Julie Bennett

Franchising has rebounded since the recession, with the nation’s franchisors opening new units at a pace of about 12,000 a year,

according to the International Franchise Association’s Economic Impact report. The report says that’s faster than non-franchised

businesses. But if you read the press releases and online promotions of dozens of brands, you’d believe that franchises are growing even

faster. In a press release last year, Menchie’s, in Encino, California, announced the frozen yogurt chain had 500 more stores in its

pipeline and was on track to open almost 150 of them in 2014.

On its website, Snap Fitness, of Chanhassen, Minnesota, claims the 24/7 fitness concept is selling 20 to 40 new franchises a month. Tom + Chee, a tomato soup and grilled cheese concept in Cincinnati that started franchising in 2013, projected by the end of 2014 it would be on pace to open one shop a week. And in 2013, Atlanta-based Schlotzsky’s announced that a factory owner in Riverside, California, had signed on to build 170 of its

restaurants in Southern California. At the time, the franchisee, Moe Vazin, said he expected to have all of them open by 2018. So far, there are seven Schlotzsky’s in Southern California. Menchie’s, Snap Fitness and Tom + Chee are also short of their projections.

What happened to all those promised units? As the recession waned and credit became looser, hundreds of franchisors went on selling sprees. Snap Fitness salespeople, for example, suggested that new franchisees sign on to open not a single gym, but a trio of units called a three-pack. Many other franchise concepts, including most hair salons, also sell three-packs, while restaurant and retail franchisors sell larger development rights to franchisees who agree to build scores of outlets within specified time

periods. If all those franchisees actually opened the units they signed up for, individual brands would be far bigger and franchising in

general would be growing much faster than its current rate. Instead, thousands of franchise sales fall into another category, called

Sold But Not Open (SBNO).

Franchisors must report unopened units each year in their franchise disclosure documents (FDD). We asked FranchiseGrade.com, a research and analytics company in London, Ontario, to provide a list of the 50 franchisors with the greatest numbers of Sold But Not Open units from its database of FDDs from more than 2,400 systems. In their 2013 FDDs, the top 50 SBNO franchisors alone reported 12,697 unopened units. Many of these units will never open because the franchisees who signed the agreements—and usually paid upfront franchise fees—are struggling to operate the one or two units they have opened; are having trouble finding sites for additional units; have lost interest or, in some cases, have run out of money and filed for bankruptcy. The most obvious victim when units don’t open is the franchisee, who might have opened a single unit and flourished. But the

franchisor also suffers, because the same territory could have been sold to other franchisees who might be thriving there. And franchising itself suffers, because more robust growth could strengthen the industry’s position in its legal battles against minimum-wage increases, healthcare reform and worker unionization.

Emptying the pipeline

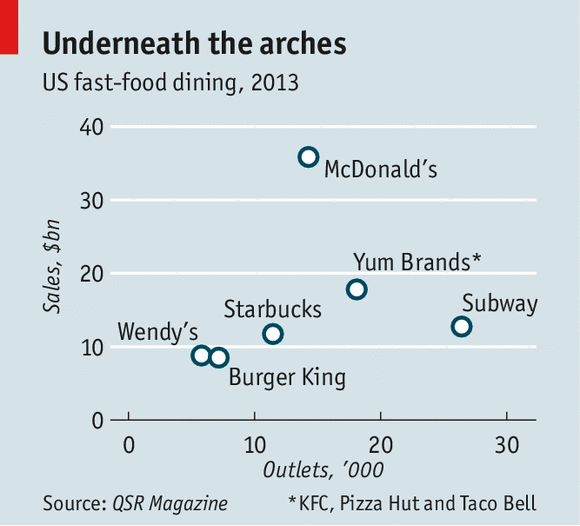

Of course, many of the SBNO units from FranchiseGrade.com’s list have since opened or will soon. Subway, in Milford, Connecticut, for example, with 1,093 SBNO units at the end of 2013, opened 788 new sandwich shops last year, or 72 percent of its backlog.

But Five Guys Enterprises, of Lorton, Virginia, which tops the list, with 1,198 units sold but not open at the end of 2013, opened only 56 new franchises in 2014, or 4.7 percent of its backlog. Five Guys sold out all its U.S. territories years ago and some of the franchisees who purchased development rights are opening new restaurants right on schedule.

But competition in the “better burger” space is fierce and some Five Guys franchisees, including groups in Ohio and Florida, are closing stores instead and a franchisee group in Fort Lauderdale filed for bankruptcy protection in 2012. One franchisee opening on schedule is Marc Magerman, CEO of Massachusetts Burger Enterprises in Natick, Massachusetts. He

said he and three partners signed a contract to build 20 Five Guys in eastern, central and western Massachusetts in 2008 and have 12 open with the 13th under construction. “It was easier to open stores when we started and had our whole territory to choose from,” he said. “Now we have to be careful not to cannibalize an existing store, yet be as close as we can be to our

competitors.” (Five Guys corporate declined to comment for this article.)

Competition is also growing in the fitness sector and franchisors are offering incentives to new franchisees to sign on with their

concepts. At Snap Fitness, for example, CEO and founder Peter Taunton said it charges a franchisee fee of $19,500, “but offered franchisees three units for a discounted fee of $45,000, which they paid upfront. A lot of people bought three-packs just before the recession and never opened their second or third gyms.” In 2013, 130 franchisees were terminated or left Snap Fitness on their own; another 206 had paid franchise fees, but left before opening a single gym. Snap’s closest competitor is Anytime Fitness, a 24/7 gym concept in Hastings, Minnesota, with 329 units SBNO at the end of

2013; of those, 190, or 57.8 percent, opened in 2014. Anytime’s national media director Mark Daly said Anytime also sells multiple territories “but only to highly vetted franchisees. Less than 2 percent of our clubs close each year.” Anytime ended 2013 with 1,681 units, according to its 2014 FDD, and 222 franchisees were “terminated, canceled, not renewed or otherwise ceased to do business.”

Getting distracted

Tony Lutfi is CEO and president of Marlu Investment Group in Elk Grove, California, and has more than 150 franchised restaurants in eight states. He said newer operators can find it difficult to fulfill aggressive development schedules. “While operators are still struggling to meet their financial objectives for their first units and need to place a greater focus on operations and marketing, they get distracted by the pressures to build more stores,” he said. Instead of building an empire, many

franchisees end up with nothing at all.

“Development agreements tend to be better for franchisors than franchisees,” said Robert Berg, chairman and CEO of Interfoods

of America, in Miami, a multi-unit operator of almost 200 Taco Bells, Popeyes and Burger Kings. “Time and time again, we see

inexperienced, overconfident new franchisees sign agreements that are beyond their ability to fulfill.”

Two hair salons, Sport Clips, in Georgetown, Texas, and Great Clips, in Minneapolis, are high on the list, at No. 6 and 8, respectively. Sport Clips had 771 units SBNO at the end of 2013 and opened 152 franchise units in 2014, or 19.7 percent, leaving the company with a four-year backlog. CEO Gordon Logan said the SBNO number includes franchisees who are still completing their contracts for three-packs or larger development deals. He added, “over 90 percent of the licenses we award get built.” Great

Clips, which opened 23.7 percent of their 1,070 sold units in 2014, declined to comment.

Many franchisors and industry insiders defend the selling of three-packs and larger agreements as the best way to grow a franchise system. The Joint, a chiropractic center franchise in Scottsdale, Arizona, had 204 SBNO units at the end of 2013 and opened 73, or 35.8 percent of them in 2014. The Joint President David Orwasher said, “We have grown from eight to 246 clinics since 2010 by asking franchisees to open multiple units in an organized fashion, driven by a penetration schedule that is

intelligently implemented.”

Ben Amante, principal of Amante Franchise Consulting in Newport Beach, California, agreed that “carefully thought out development plans” can be beneficial to franchisors and their multi-unit franchisees. “But,” he said, “many of those sold units exist just on paper, because the salespeople who sold them focus more on their own commissions. They approach people who just qualified to open one unit and say, ‘Why stop there? I can give you a discount on two, or 10 more units, and you can build an empire.’”

“A franchisor may find it’s easier to sell the dream than the reality,” said Oak Brook, Illinois-based franchise attorney Michael Liss.

“Some franchisors ask new franchisees to sign development schedules without having opened that many stores at that pace

themselves.”

Stuffing the channels

The top five franchises with sold but not open units, according to FranchiseGrade.com and a Franchise Times analysis, are: 1.

Five Guys, with 1,198 SBNO units at year end 2013, and a 4.7 percent open rate in 2014. 2. Quiznos, with 137 SBNO and an 8 percent open rate. 3. Moe’s Southwest, 383 SBNO and a 16.4 percent open rate. 4. Zounds Hearing Center, with 105 SBNO and an 18.1 percent open rate. 5. Menchie’s, with 385 SBNO and an 18.4 percent open rate in 2014.

John Gordon, founder and principal of the Pacific Management Consulting Group in San Diego, said, “Wall Street likes to see a full pipeline, so franchisors tend to stuff their supply channels before they seek private equity investors or an investment banker to take them public. Franchisors backed away from selling big territories during the recession when franchisees were missing their targets big time, but many are again under pressure to show they have growth potential.”

Justin Klein, an attorney with Marks & Klein in Red Bank, New Jersey, noted franchisors who set unrealistic development schedules are ultimately hurting themselves. “This is one area where franchisees and franchisors should work together, sharing the common goals of growth and putting up more units.” Klein said.